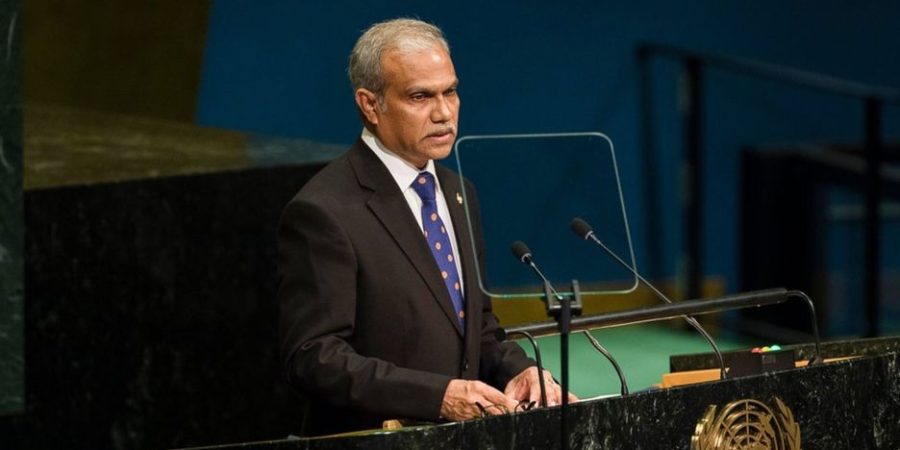

Why the Maldives has quit Commonwealth? By Mohamed Asim

Last year, at the meeting of the Commonwealth Heads of Governments in Malta, that organisation’s chair, Queen Elizabeth II, reflected on the strides member nations had made since its inception. She praised “the forging of independent nations” and how “many millions of people sprung from the trap of poverty, and the unleashing of the talents of a global population.” But a year later, the organisation continues to struggle with increasing scepticism about how membership offers any tangible benefits to smaller states.

The Queen was certainly right in her speech. Huge progresss has been made since the 1949 London Declaration. Yet this week the Maldives – a constructive and engaged member since 1982 – left the Commonwealth. As someone involved in this decision, it was an extremely difficult one to make, but our Government was left with no practical alternative. Our story offers a window into why this organisation requires fundamental reform – reform it needs more than ever in the post-Brexit era.

Ever since joining in 1982, the Maldives has viewed the Commonwealth as a force for good and a vehicle for opportunity. As one of its smallest nations, the Commonwealth’s charter offered us hope for new links to the outside world and a chance to strengthen institutions. We saw the value of the Commonwealth’s mission to cultivate the values of democracy in young nations.

But as an association born in the twilight of the empire, the Commonwealth has shown surprisingly little empathy towards the struggles of post-colonial states such as the Maldives. Most of its member nations are half a century old; their institutions are young and often imperfect. The tradition of the ballot box has been universally embraced – even if it took decades to properly bear fruit. It is worth remembering how long it took in one of the oldest democracies of all – Great Britain – for women to become enfranchised.

Yet this realism has fallen on deaf ears. No one can deny that the Maldives has faced challenges in recent years. We remain open to outside scrutiny, and the frequent political demonstrations in our capital, our vibrant opposition media, and our visits of high ranking officials and human rights organisations are all examples of that. And yes, our judiciary, parliament and civil society need further professional development.

But this is not unusual. From Asia to Africa and the South Pacific, these challenges are universal. Many members have also witnessed civil conflict and political upheaval. Regrettably, the Commonwealth decided to take a punitive stance on the Maldives rather than one of constructive dialogue and institutional development.

The decision came despite the fact that the resignation of our former president in 2012 represented a transfer of power that a Commonwealth-backed Commission of National Enquiry declared lawful. The multi-party elections that followed were also recognised as free and fair – by the Commonwealth. So the resulting hard line has left many of my compatriots collectively scratching their heads.

Sadly this kneejerk grandstanding is symptomatic of the modern era Commonwealth. Its budget has shrunk year-on-year, meaning programmes to improve governance or increase development have fallen by the wayside. That work was replaced by the ever more active and ideological Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group (CMAG) which, along with the Secretariat, has become embedded in the political discourse of smaller member states. This has helped the Commonwealth leverage its way into international diplomacy.

But the organisation’s desperation to remain relevant should not mean it morphs into an unaccountable global police force. If the Commonwealth really wanted to engage, it would see progress is being made on our islands.

This Government has enacted a total of 110 pieces of legislation in the last three years, 94 of which were directly related to the core values set out in the Commonwealth Charter. And 69 were specifically designed to promote human rights, strengthen democratic governance, and to reinforce the separation of powers. If this is not progress, I do not know what is.

The door will always remain open to our friends at the Commonwealth. We cannot forget the deep historical ties with Great Britain and her allies. The Maldives provided crucial logistical support during the Second World War and during several other engagements that Britain has fought since then. Our hand of friendship remains extended.

But we hope our decision to leave the Commonwealth spurs a reassessment of its role in the 21st century. Smaller nations have fallen victim to the Commonwealth’s march to become relevant. The project of nation building has been forgotten.

Its own charter describes an “association of independent and equal sovereign states, each responsible for its own policies, consulting and co-operating in the common interests of our peoples and in the promotion of international understanding.” Our experience shows this philosophy has been all but abandoned. Let us hope that these founding principles are rediscovered and resurrected. Then perhaps other nations like ours would not have to take the actions that we were forced to this week.

Mohamed Asim is the Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Maldives

Related News

President Sisi affirms Egypt’s support for Lebanon

CAIRO, Mar 11: President Abdel Fattah El Sisi made a phone contact with Lebanese PresidentRead More

B-52s arrive at UK air base amid conflict with Iran

DNA LONDON: Three more US bombers have landed in the UK after Prime Minister SirRead More

Comments are Closed